The Best Way to Rob a Bank Is to Own One gives the perspective of a regulator and criminologist on the looting of banks in the lead up to the Savings & Loans Crisis. The ubiquity of fraud during this period reveals patterns of behavior that can be systematically examined. This phenomenon is chunked into the framework of control fraud, a particular type of fraud where a company becomes a vehicle for enrichment of related parties while simultaneously undermining the viability of the company. Black highlights the context and subtexts of fraud, which helps to make control fraud a useful framework to analyze many situations in public markets.

I am going to summarize the mechanics behind the S&L control frauds and then revisit recent episodes that illuminate the adaptations of control fraud in the stock market. The key ingredients of control fraud that Black identifies – accounting abuses, rapid growth, ease of gaining control, and lax regulation – are enduring in public markets. Carvana, Valeant, and the SPAC craze of 2021 are three examples that demonstrate what happens when they all combine.

Control Fraud in S&L’s

The model of borrowing short and lending long is particularly dangerous when interest rates quickly increase. S&L’s focused on taking in short term consumer deposits and writing long term mortgages on homes. These mortgages drove banks to insolvency when Volcker raised interest rates in the early 1980s. This set the stage for banks to become vehicles for extraction.

Richard Pratt was appointed in 1981 as the chairman of the Federal Home Loan Bank Board (“Bank Board”), the body responsible for overseeing most S&L banks. His regulatory philosophy was aligned with Reagan, who had appointed him. Pratt made several deregulatory moves to defer recognition of the industry’s widespread insolvency.

Regulators permitted accounting that helped convey the appearance of good health. Two insolvent banks could merge and instantly create a seemingly better capitalized entity, which would temporarily stave off regulatory intervention. The capital hole of the acquired bank could be recorded as goodwill on the acquirer’s balance sheet, which counted towards capital at the time. The logic was that the market value was whatever someone was willing to pay. This flattered the efforts of regulators to increase bank solvency without the government bailing anyone out even though loss absorbing capacity never increased.

Real estate owners were allowed to contribute properties that could count as a capital injection into a bank. This is where a lot of people who were subsequently convicted for fraud entered. These property injections were assigned inflated values by friendly assessors and auditors. An opportunist could recapitalize a bank in need of $5m with a property aggressively appraised at $25m. The bank would gain $5m of capital and the property owner would receive cash for the “extra” $20m. The increase in capital was illusory as cash worth $20m left the balance sheet in exchange for $5m of real value. This bank could then merge the bank with other insolvent banks, further exacerbating the capital hole.

More rules changes included removing restrictions on one individual from owning or controlling an S&L. It also became easier for a bank to lend more than 100% of net worth to a single borrower. Rules that would have prevented related party transactions were relaxed. Limitations on construction lending, which is an area where third party valuations can be particularly fantastical yet legitimate seeming, were eased so that banks could increase their relative exposure to it. It became easy for an individual to obtain control of a bank and extract money.

Capital requirements, the most basic governor of bank growth, perversely encouraged even faster growth amongst the worst intentioned. Banks could use their five year trailing average of liabilities to determine if they were in line with a 3% capital minimum. This meant faster growth required proportionately less capital. Newly created banks had a 20 year phase in for capital – e.g. they only need 1/20 their required capital at the end of their first year, 1/10 the second year, and so on. This meant the fastest growth required close to no capital to support any potential defaults.

Rapid growth was easily manufactured through Acquisition, Development, and Construction (“ADC”) lending. An ADC loan covered the acquisition of the land, then its development to accommodate buildings (sewers, utility lines, roads), and finally the construction of a building that would theoretically lead to refinancing the loan as the building generated cash flow. You just need raw land to start handing out money. The profits of an ADC loan could be front-loaded while the risk of loss from defaults was deferred as the higher interest rates and upfront fees could initially be paid from the proceeds of the loan rather than cash flow or refinancing a completed project. ADC lending exploited all the discussed regulatory loosening in addition to inherently aggressive accounting. The ADC ponzi is an illustrative demonstration of how the key ingredients of control fraud interact with and amplify one another.

This sequence of seemingly productive economic activity was hijacked and turned into an extraction mechanism. The terms and conditions of ADC loans resulted in ADC loans being a great vehicle for extracting money from the bank. Per Black;

“There was no down payment.

There were substantial up front points and fees.

All of those points and fees were self-funded: the S&L loaned the buyer the money to pay the S&L the points and fees.

The term of the loan was two to three years.

There was no repayment of principal on the loan prior to maturity. (The loan was interest only, or nonamortizing.)

The S&L self-funded all of the interest payments. The S&L paid itself the interest when it came due out of an interest reserve. The S&L increased the borrower’s debt by an amount equal to the interest reserve.

The interest rate on the loans was considerably above prime.

The borrower had no personal liability on the debt (the loan was non-recourse). His construction company was indebted, but the developer was not. He did not provide any meaningful personal guarantee of his company’s debt.

The developer pledged the real estate projects (the collateral) to secure the loan.

The loan amount equaled the (purported) value of the collateral.

It was common for the borrower to receive at closing a developer’s profit that could represent up to 2 percent of the loan balance.

It was common for borrowers to give S&L’s an equity kicker, an interest in the developer’s net profits on the projects. At first, these kickers often exceeded 50 percent. After the accounting profession issued a “notice to practitioners” that said a 50 percent equity kicker was evidence that the transaction was not a true loan, it became common to give a 49 percent interest.”

The many features of ADC loans were a magic trick where a snapshot of the bank’s financial state concealed a rapid escalation in risk. The borrowers willing to accept these terms – very high interest rates, equity kickers, substantial fees – were the weakest. The self-funding of interest payments could obscure the poor credit of the borrowers for a period of time. There is no natural limit to growing rapidly when giving out loans to borrowers who don’t have other options. It was as easy to make it look profitable for a period of time as it would be hard to permanently conceal the disastrous nature of the loans. This is a good demonstration of the adverse selection that underlies a lot of the rapid growth, which is why it ultimately produces large losses.

One way ADC borrowers were able to extract lots of money was the “land flip.” A daisy chain of transactions on a property occurs in rapid succession until a large per acre price is paid. This creates a market value that can be lent against. The eventual purchaser could be a land developer that plans to build thousands of townhomes but uses the loan proceeds to hire related entities at outsized mark ups. The various entities that take money out through mark ups on related party transactions represent straws that allow for control frauds to extract money with a veneer of propriety that further undermines the solvency of the controlled entity.

Edwin Gray, Pratt’s successor who started to push back against abuses in the S&L industry, had a Texas real estate expert survey construction lending done along I-30, where Empire Savings and other copycat banks supported the land flips, in early 1984. The film offered a panorama of incomplete projects along the highway in Garland, Texas. There were thousands of units in various stages of completion that represented over a decade of demand (paper on Empire). This evidence was among the many reasons regulators started to push back on S&L control frauds, although it took several more years for many of the banks to finally collapse under the cumulative weight of their intentionally poor decisions.

Ecological Considerations

Control fraud often lacks a natural predator. It weaponizes the instincts and inertia of other organisms with which it interacts. Reagan, the S&L industry, Congress, and the public were not interested in a liquidation of the S&L industry when it first became insolvent. Recognizing it ran counter to Reagan’s ideology and political calculations. No industry wants to admit it is insolvent, especially one that operates almost entirely on confidence. Every congressional district has a bank. Every voter wants easy access to home loans to realize the American Dream. Houses are built by construction workers and developers then sold by realtors, all of whom are present and vocal in every congressional district. While financial firms are very ripe for control fraud, politically profuse entities that serve the purposes of many other interest groups is probably a more accurate test for ripe conditions. Free money upfront with deferral of the true costs results in viral commercial activity, both in its rapid spread and eventual hobbling of its hosts.

The way a control fraud enlists the ecosystem’s self interest was particularly well documented in the aftermath of the S&L collapse as a result of government investigations. It was not contemporaneously hidden either. In 1985 Alan Greenspan was an expert called on to provide opposition to Gray, who was pushing for stricter regulation of S&L’s. Greenspan was paid by Keating, of the notorious Lincoln Savings, to conduct studies “proving that faster growth and greater direct investments produced higher profits and healthier S&L’s.” Gray, who was initially appointed as a staunch Reagan ally, moved to clamp down on the basis of tangible evidence such as the 1984 I-30 footage. Gray had shown I-30 land flip video to Paul Volcker who, according to Black, was “horrified,” which is a decent contemporaneous corroboration that Greenspan’s judgement was intellectually dishonest and corrupt.

Greenspan defended his actions in 1989. His evasion of responsibility through diffusing the blame reveals how the ecosystem was enlisted in support of control fraud. Greenspan’s opinion was for sale, along with lawyers, accountants, and politicians who could all plausibly deny responsibility by pointing fingers.

In a Feb. 13, 1985, letter to the Federal Home Loan Bank of San Francisco, Greenspan argued that Lincoln deserved an exemption from regulations limiting to 10 percent thrifts’ direct investment in real estate and other commercial ventures.

Lincoln’s management, he said, was ″seasoned and expert in selecting and making direct investments″ with ″a long and continuous track record of outstanding success.″ The institution itself was ″financially strong,″ in a ″vibrant and healthy state″ and ″present(ed) no foreseeable risk to the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corp.,″ he said.

Two weeks later, on Feb. 27, 1985, Greenspan told the House Government Operations subcommittee on consumer, commerce and monetary affairs that direct investments, while undoubtedly risky, were essential for thrifts to diversify their holdings.

Traditional S&Ls, which took in short-term deposits and made long-term mortgage loans, were vulnerable to a sharp rise in interest rates and direct investments were a valuable alternative, he said.

He also endorsed a study by economist George Bentsen, now with Emory University, which cited the success of 17 S&Ls in direct investments. Fifteen of the 17 have since failed.

″It was my view then, as it is now, that interest rate risk was the crucial problem confronting S&Ls - the problem of long-term assets financed by short-term deposits. In that particular context, at that particular time, direct investment would reduce risk,″ he said.

Greenspan still believes Bentsen took a ″rather sensible statistical approach″ but he points out that most of the 17 S&Ls cited in his study were located in Texas, later the center of the oil and real estate bust.

The central bank chairman’s views have been cited as one of the reasons why a petition, calling on S&L regulators to postpone direct investment limits, attracted 225 signatures in the House in early 1985.

It is also being cited as a reason why, two years later, five senators decided to intervene with S&L regulators after Keating complained about their efforts to examine Lincoln’s finances.

The five - Alan Cranston, D-Calif.; Dennis DeConcini, D-Ariz.; Donald W. Riegle Jr., D-Mich.; John Glenn, D-Ohio, and John McCain, R-Ariz. - met with the regulators in April 1987.

Two of them - Cranston and McCain - said Greenspan’s views on Lincoln’s health heavily influenced their thinking.

″The problem, as conveyed to me at the time, not only by Mr. Keating but also by Mr. Greenspan and Arthur Young & Co. (an accounting firm) was that federal examiners bore substantial responsibility for creating a most destructive and irrational state of limbo for this institution,″ Cranston told the Senate Ethics Committee in a Nov. 16 letter.

Greenspan said he does not understand why the senators cite his opinion as a reason for actions taken so long after it was given.

″You do not rely on a 2 1/2 -year-old letter unless you call the guy who wrote it. No one ever called me,″ he said.

Greenspan, as president of Townsend Greenspan & Co., was hired to review Lincoln’s condition by the New York law firm of Paul Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison. He said he could not remember how much he was paid for his work, but said he charged his usual hourly rate.

The partners of the law firm, he said, were long-time, trusted associates. ″They certainly never gave me the slightest impression that these were other than good people″ at Lincoln.

Greenspan said he recalls meeting Keating himself two or three times, but never for a detailed, analytical discussion. The people working under Keating ″frankly I found fairly impressive,″ he said.

Questionable behavior appears relatively more acceptable when nobody appears to be interfering with it and a diverse array of professionals are endorsing it in a circular fashion. As more people facilitate a control fraud environment, it diffuses responsibility so widely as to make most people immune to any existential risks. This procyclical ecology reinforces the rapid growth that also typifies control fraud, creating a temporarily symbiotic relationship between a growth at all costs organization and a political context that temporarily amplifies it for its own benefit through lax regulation.

Contemporary Control Fraud

Contemporary control fraud gives sharp definition to situations where a security represents a vehicle for extraction rather than a business that will distribute profits to shareholders. There will always be a tussle over how the economics of a business get distributed (principal-agent problem). At some point the insider enrichment ends up being diametrically opposed to cultivating a sustainable business. Identifying the four key ingredients of control fraud - accounting abuses, rapid growth, ease of gaining control, and lax regulation – is a very strong sign that impact of control fraud is about to felt even if the intent can’t be proven.

Carvana

The comparison that remained constantly at the front of my mind while reading Black’s book was Carvana. All the key ingredients of control fraud interacted with one another to result in shareholders nursing losses while the controlling parties dramatically increased their wealth.

Rapid Growth

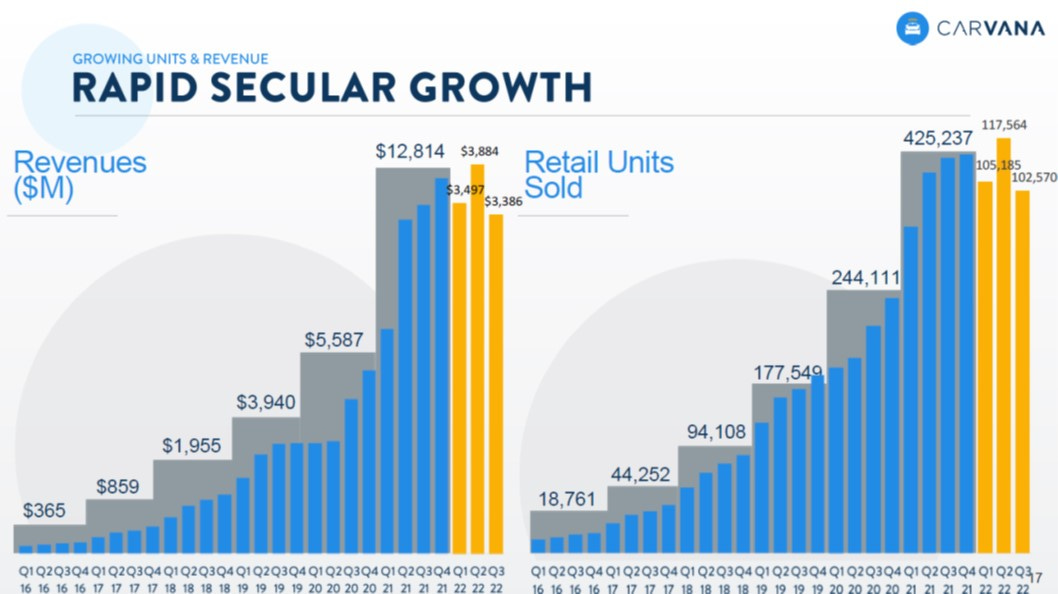

Carvana targeted rapid growth as an analog-to-digital ecommerce play in a large retail vertical with the goal of capturing a winner-take-most reward. Carvana’s revenue grew 350% from 2017-2019. COVID helped fuel massive growth in all areas of ecommerce and Carvana was no exception. The triple benefit of quarantining boosting ecommerce, broad stimulus for consumers, and the acute shortage of cars were a massive tailwind for Carvana to show a continuation of rapid growth in its business with 225% revenue growth from 2019-21. Management prominently touts this element of the business.

In Carvana’s framing, the used auto industry has the potential to resemble other retail categories where ecommerce resulted in winner take most dynamics. The logical extension of the business from a low single digit to potentially 30% market share primed markets to extrapolate rapid growth for many years. Not only was this rapid growth, but it was secular – Carvana could go from 400,000 units to 12,000,000 in the future, a 30 fold increase, if used car retail reflected other retail verticals.

Abusive Accounting

“Statistics are like bikinis. What they reveal is suggestive, but what they conceal is vital.”

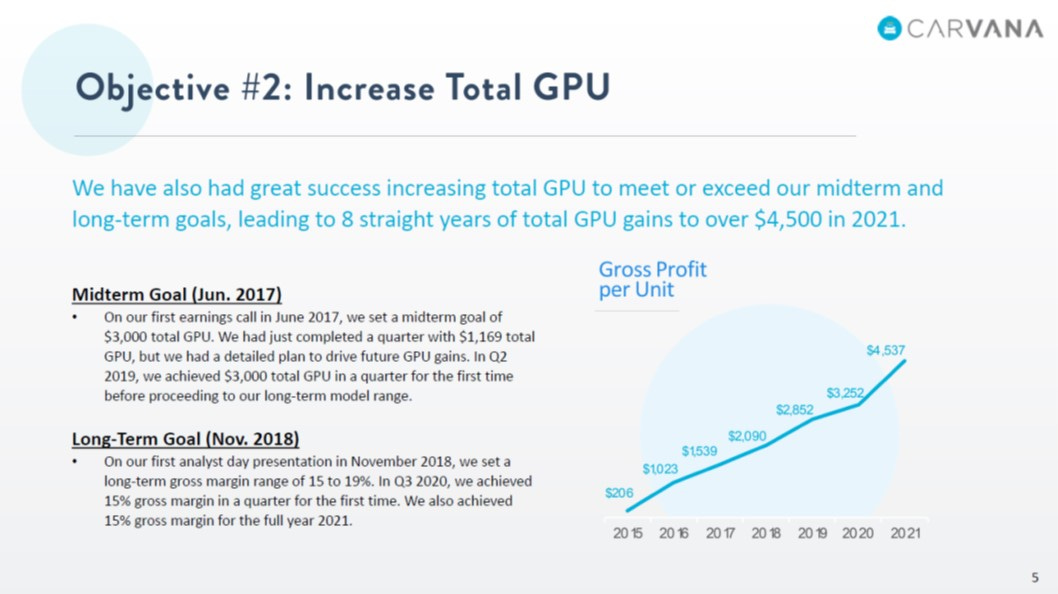

Carvana management referred investors to the gross profits of the business and then provided projections of the operating expenses in a future normalized state. Management invited the market to view operating expenses as something to expect becoming more fixed in nature at some point in the future to be followed by operating leverage that eventually generates massive profits. Under this pretext, management treats gross profits as a plausible window into the potential economics of the business, which makes the rapid growth the necessary means to realize it.

Management often presented GPU as a homogenously composed figure. While there are industrial drivers to gross profit, such as operational scale, gross profit was composed of distinct activities. About ~30% of Carvana’s gross profit relies on Gain on Sale accounting. Gain on sale accounting is connected to the business practice of securitizing or selling loans. This is driven by interest rates and broad financial markets, not by how many units Carvana may be running through its refurbishment facilities or vending machines. Merging industrial and financial factors into one line item can be viewed as aggressive accounting, as it obscures the underlying economics of the business. It is worth noting that Carmax, a competitor, reports its financing and auto retail segments separately, implying an active choice by Carvana’s management to portray the business as it does.

Carvana originates auto loans and packages them into an asset backed security. This ABS is sold to the market with a much lower yield than the origination yield. The value represented by the difference in the rate that Carvana collects and the ABS holder collects is what generates the gain on sale. The spread between origination and securitization yields may compress for a variety of factors, which would shrink the gain-on-sale. Securitization markets may also demand more credit enhancements in the form of overcollateralization to account for higher potential charge offs on loans, further reducing the amount of cash that Carvana can generate from securitizations. The nature of recognizing a gain on sale creates the appearance of greater profitability in the short term even if it is not a sustainable model longer term. This is conceptually comparable to S&L ADC lending, particularly in the front loading of profits to create an alluring financial snapshot.

Given the long experience in the used car market at Drivetime, the incubator of Carvana, management is aware of the cyclical nature of auto retail and the challenges that may emerge in a business reliant on securitizations. Ugly Duckling, Drivetime’s original name when Ernest Garcia 2 (EG2) first entered the used car business, was one of the pioneers of the subprime auto loan securitization market. Ugly Duckling declared bankruptcy during a downturn in business that evaporated gain on sale profits. This supports the framing that management was unconcerned with the long term financial health of the underlying business.

Weak Regulation

Carvana has mostly avoided a strong response from the SEC or State Transportation authorities. The statements Carvana has made about gross profits or in the prospects for the business were all made with standard disclosures about forward-looking statements. The SEC wouldn’t force them to report in more granular segments, as Carmax does between its financing and auto retail segments, even though Carvana has the same business functions, as this exceeds minimum disclosure standards.

There have been numerous state regulators frustrated by the car title transfer process at Carvana – Florida, Illinois, Maryland, Michigan, Missouri, Ohio, and Pennsylvania, to name a few. Particularly in the aftermath of COVID with car shortages, it is hard for a state level regulator to shut down a company helping people purchase cars, which speaks to the broader ecology from which Carvana benefitted. Car sales from Carvana could also originate in a different state, which meant state level regulations couldn’t be enforced, as in Colorado.

The magnitude of this behavior pales in comparison to the behavior of S&L’s, but it does show how regulators have a broader range of constituents to consider when wondering why aggressive measures aren’t immediately taken when business practices aren’t flawless. Even though Carvana itself is a “young” company, it was incubated within DriveTime, a long time used car seller that certainly would have the institutional knowledge to implement the correct operational requirements for transferring titles.

The broader subprime lending and used car retailing industries are not known for plain dealing and painless transactions, which speaks to the favorable ecology in which Carvana has operated. It is reasonable to see how Carvana does not attract regulatory attention when reading the CFPB lawsuit against Credit Acceptance, where the actions are more plainly socially objectionable for a regulator or District Attorney to allow. There is also no government entity on the hook if Carvana were to fail, which decreases the appetite or ability for the government to intervene.

Ease of Obtaining Control

The Garcia family controls Carvana through super voting shares held by EG2. Ernest Garcia III, the son of EG2, is the CEO of Carvana. Control is cemented by the corporate governance of Carvana, which simultaneously gives it a veneer of propriety. Longtime business associates of the Garcia’s are on the board, which creates continuity of control beyond Carvana’s 2017 IPO while providing some veil of independence. The audit committee head is Ira Platt, an early investor in Carvana who was on the board at both DriveTime and Bridgecrest before Carvana went public. A second audit committee member, Greg Sullivan, worked at DriveTime between 1995 and 2007, including as CEO. Ray Fidel, who was convicted in the early 1990s alongside Garcia II for bank fraud related to Lincoln S&L, was the successor to Sullivan as CEO of Drivetime from 2007 to 2015 when Carvana was being created, although Fidel is not involved with Carvana at present.

There are related party transactions between Carvana and several entities owned by the Garcia family. These transactions are overseen by the board, but this is less likely to be rigorous given the long standing personal relationships.

Drivetime has remained a major business partner for sourcing cars for Carvana. Bridgecrest is a loan servicing firm that handles loan servicing for Carvana that is owned by the Garcia family. SilverRock is the warranty provider on Carvana’s cars that is owned by the Garcia family as well. These transactions represent straws into the Carvana entity that allow the Garcia family to earn money independently of the success or failure of Carvana as a stand alone business. There may also be the inverse possibility, which is that they may be used to temporarily bolster Carvana’s financial results, although that is speculative. This is all disclosed in the company’s SEC filings and the Wall Street Journal has reported on it:

The Garcia’s took Carvana public in 2017 with agreements to pay DriveTime for various business services. Last year, Mr. Garcia II’s companies took in around $85 million in revenue from providing extended warranties to Carvana buyers, collecting on their loans, and selling or leasing real estate, according to Carvana filings.

Carvana, known for its car vending-machine towers, has continued to strike new related-party deals with companies controlled by the elder Mr. Garcia, a Carvana spokeswoman said, “because they provide the most value in delivering exceptional customer experiences and growing into our opportunity as quickly as possible.”

When Carvana was having trouble meeting customer demand this year, it bought thousands of cars from DriveTime to help catch up. To add buildings for another 1,000 employees at its Phoenix-area corporate campus, Mr. Garcia II bought the land. To help pay for inspection centers getting cars to customers faster, Carvana purchased a building from Mr. Garcia II and sold it for more.

Carvana’s spokesperson’s response to the issues raised in the WSJ article was, “‘at certain companies, there may be concerns with related-party agreements creating risks for investors,’ but she said the roughly 20 times increase in Carvana’s stock since its initial public offering has ‘presumably resolved any potential concerns.’” This hints at the ecology of control fraud. The appearance of no issues is validated by some loosely objective measure like a market value and shallowly independent oversight, which has strong echoes of S&L control fraud obfuscation.

One reason to be fixated on the share price is because it can represent an avenue of extraction. The Garcia’s have been constant net sellers of shares in large quantities. Share sale proceeds for EGII add up to ~$4bn, far in excess of purchases. While EGII was already a seller prior to COIVD, he became a significant seller in 2021 as the excitement over Carvana’s growth and prospects propelled the company to a massive valuation.

Rather than raise additional funds for Carvana to sustain its business and solidify its financial position, insiders sold their personal shares. The company was unprofitable even in one of the most favorable backdrops for the used car market in 2021. The company could have conducted an equity raise when the market was very receptive to Carvana’s story. Instead they raised additional debt and equity in the middle of 2022 after the share price had fallen and the cost of debt had increased. This could be viewed as a strong indication that the shares represented a vehicle for extraction by insiders rather than a long term sustainable business that would distribute profits to all shareholders.

While this is simpler than how opportunists enriched themselves in the S&L era, it is sophisticated in how it sidesteps easily identifiable criminal activity. The market’s attraction to the Carvana story for a period of time was enough to drive up the price and allow insiders to sell their shares. If as La Rochefoucald says, “the height of cleverness is the ability to conceal it,” then the Garcia’s are quite clever in how they have used their control of the company to enrich themselves.

Valeant

Valeant is another good example of the finer points of contemporary control fraud. There was a confluence of aggressive accounting, aggressive drug pricing actions that regulators and insurance companies were slow to respond to, large compensation packages tied to share price, and rapid growth. The share price climbed up from ~2010 until late 2015 before collapsing.

Abusive accounting

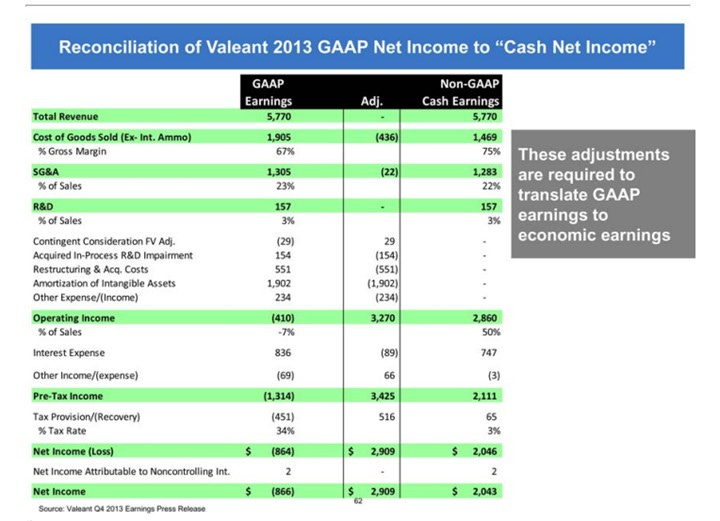

The Valeant situation emphasizes the arbitrage of what one can say in a presentation with a disclaimer compared to financial statements submitted to the SEC. While unpacking Carvana’s gross profit obfuscation requires some familiarity with securitization dynamics through an entire cycle, Valeant’s abusive accounting was more transparent.

Valeant used adjusted earnings to excite the market. Bill Ackman of Pershing Square simply repeated the companies adjustments and explanations when presenting the idea in 2014. A loss of $864 million suddenly turns into a profit of $2.9 billion. While accounting standards were very permissive during the 1980s in ways that aided insiders’ looting of S&L’s by delaying regulatory intervention, the current permissive attitude is rooted in broad market acceptance of adjusted figures. Metrics given in a presentation can dominate the narrative of business even when they run counter to what SEC filings show. There is a lot more leeway before crossing legal boundaries when all the proper disclosures are made and the market simply chooses to ignore them.

The misleading nature of these figures was contemporaneously evident with a basic understanding of the pharmaceutical industry. Pharmaceutical companies need to make ongoing investments to retain the same level of profitability in the face of patent expiry on key drugs. Whether a new drug is brought to market via internal R&D or acquisition of an already approved drug, both represent an ongoing investment in the maintenance of the existing business. Adding back amortization of intangible assets was misleading because the amortization reflected the absence of R&D expensed through the income statement. Moving R&D to the cash flow statement via acquisitions recorded under cash from investing did not change their essential nature to the ongoing business. The necessity of acquisitions to sustain the same level of business makes the restructuring and acquisition costs an ongoing part of the business.

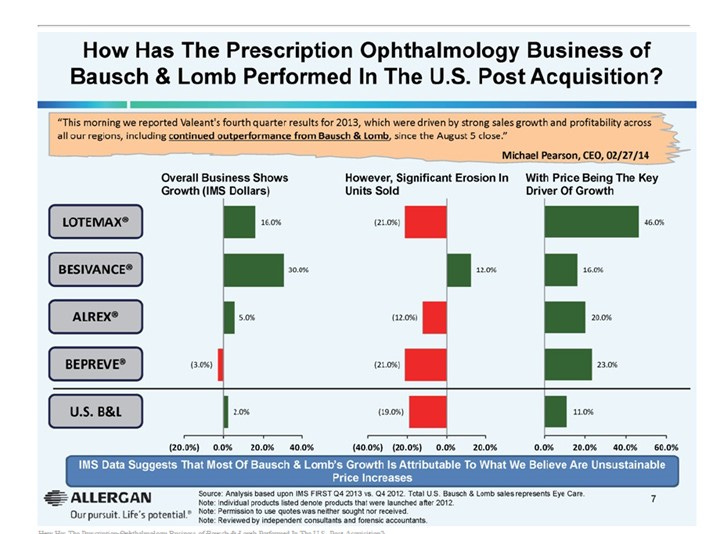

Rapid growth

Acquisitions were critical to creating the appearance of Valeant’s rapid growth and supporting the misleading accounting the company promoted. Allergan drew attention to many weaknesses in Valeant’s business, including how the company’s pricing strategy was causing volume to decrease, in a May 2014 presentation defending itself against a hostile takeover by Valeant. While this would typically be in an industry database or require hands on industry expertise to identify, it became available to everyone. The day Valeant acquired Nitropress and Isuprel, the prices increases 525% and 212% - which helped temporarily sustain growth. This behavior was reported in the WSJ in early 2015 as the share price rocketed upwards.

Valeant presented the acquisition strategy as generating great cash paybacks. AZValue in August 2015 in two blog posts laid out why the payback timelines and IRR claimed by Valeant in presentations was mathematically absurd. Amongst other issues, AZValue also pointed out how the revenue growth Valeant claimed on acquisitions was given as an the unweighted amount – 12% vs 6% weighted - which is overly flattering and hints at a broader appetite for deception.

The large price increases had the similar effect of ADC lending. It puffs up current year results and increases the risk that the business falls off a cliff in the future. Customers and competitors in any industry typically respond to massive price increases. This can introduce existential risk if acquisitions are mostly debt funded, as Valeant’s were.

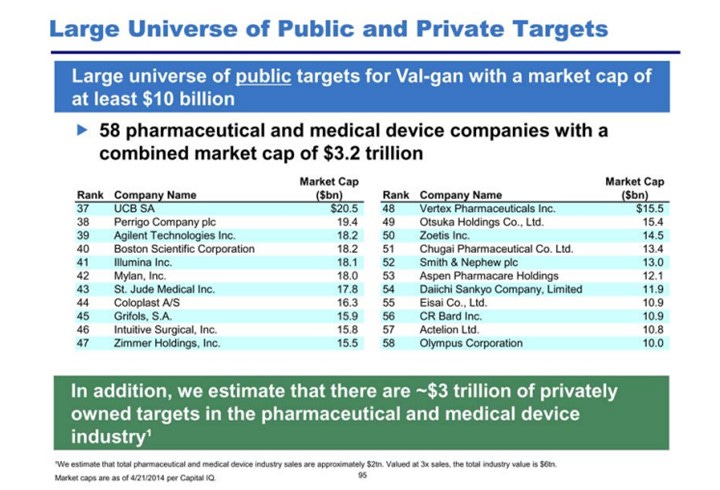

Similar to Carvana’s perceived large opportunity for rapid secular growth by capturing 30% market share, Valeant had a large number of acquisition targets to which it could apply its formula to the tune of $6trn of targets between pharmaceutical and medical device companies in the private and public space.

Lax regulation

Lax regulation was critical to facilitating Valeant’s pricing driven rapid growth. Valeant used a wholly owned specialty pharmacy called Philidor to conceal this behavior. Philidor routed prescriptions for Valeant drugs in a way that made it difficult for insurance companies to push back on price increases, at least for a period of time. Insurance companies stopped doing business with Philidor when these practices received greater scrutiny. This is partly a reflection of the relative lack of government involvement in the US healthcare system, as Valeant explicitly avoided Western Europe where it is unlikely healthcare regulations would have permitted Philidor’s maneuvers.

Auditors ignoring poor disclosure around Valeant’s transactions with Philidor reflects another regulatory shortcoming. Valeant had a zero cost option to purchase Philidor for which they paid $100m, which has all the substance of an acquisition. Valeant pushed the interpretation that it was not wholly owned and therefore didn’t need to be fully consolidated. The option allowed for the creation of the illusion that the entity’s results shouldn’t be consolidated, which obscured its role in the business.

When Philidor was publicized, the company admitted it represented ~7% of quarterly revenue and a larger portion of revenue growth. Valeant then announced they were “ending their relationship” with Philidor, an admission it was unsustainable and couldn’t withstand public scrutiny. Given the role Philidor played in obtaining high prices for drugs, it also likely represented a disproportionate amount of profits, both GAAP and non-GAAP.

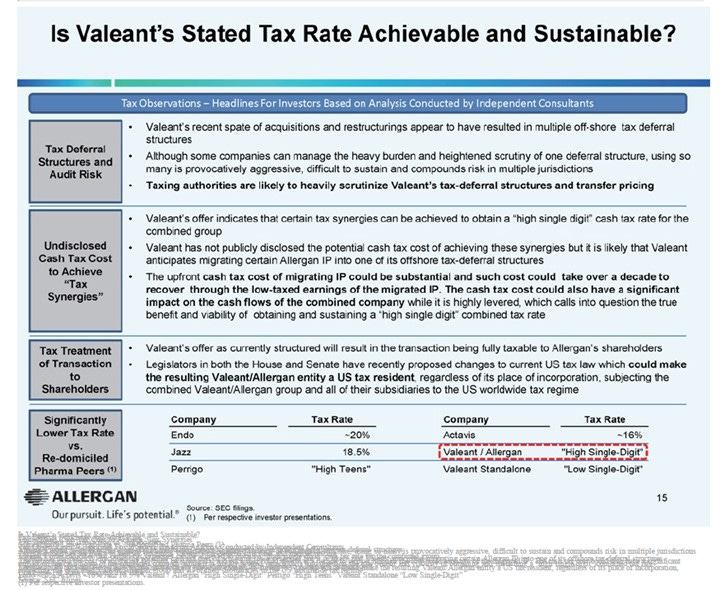

Tax regulation was yet another area that Valeant seemed to exploit. Allergan’s aforementioned presentation credibly pointed to Valeant’s tax strategy as likely to come under additional scrutiny. This contrasted to Pershing Square’s 2014 presentation where they claimed to have done due diligence on the company’s tax structure with no supporting evidence. Claims to a low single digit tax rate stood out even relative to similarly domiciled peers. In the context of Valeant’s other deceptions that defied common sense, this is unlikely to have been any different. The passage of the Base Erosion and Anti-Abuse Tax (BEAT) in 2017 instituted a 10% minimum, which at least technically shows that a single digit tax rate would not have proven sustainable.

Ease of control

“When you’re a star, you can do anything you want.”

The ease of control angle at Valeant was more subtle than super voting shares, injecting overvalued properties as capital, or incubating the company inside a large organization. Several investment firms - ValueAct, Pershing, and Ruane Cunniff - had generated large profits on their Valeant shares or from a relationship with Valeant at points in time. The presence of prominent investors bolstered the stock and the company’s reputation while Pearson profited from his options package increasing in value. This resembles an investor microecology to the macroecology of political constituents seen in the S&L scenario; a collection of myopic parties who benefit from the misrepresentation without being explicitly complicit in it in a way that prevents forcing a change of course.

ValueAct owned a large stake in Valeant for many years, hired Pearson, and gave him a large compensation package tied to the share price. This was praised in the WSJ in 2009. The plan required the share price to go up at a high rate for the options to vest, as did subsequent iterations of the compensation plan. The shares had gone up dramatically by 2015, which created a permissive attitude around his actions, which included pledging shares that were eventually margin called. By borrowing money against the shares, Pearson could generate large sums of cash for himself with little regard for the sustainability of the business – e.g. getting 30 cents on the dollar for something that is really worth 10 cents is still a gain.

Pearson enlisted the support of another hedge fund, Bill Ackman’s Pershing Square, by alerting Ackman to Valeant’s impending big for Allergan, which netted Ackman $2.2bn of profits after giving $400m to Valeant in 2014. In early 2015, Ackman became a shareholder after being impressed at having to pay for his own Chipotle lunch when he visited the company’s offices. In August 2015, Valeant purchased Sprout, a “female Viagra” company that Ackman had personally owned 1.5% of after investing in its most recent funding round prior to being acquired (Valeant purchased Sprout for $1bn and ended up giving it away two years later). Ackman was then a public defender of Valeant in late 2015 when the Philidor information became public with another powerpoint presentation.

Ruane, Cunniff & Goldfarb is an investment firm with a reputation for doing extensive independent research and having a connection to Warren Buffett. While not involved at the board level, they had owned the shares for many years and temporarily had a large profit on their shares, which also represented 32% of their portfolio at its peak. Two of the funds outside directors, one of whom considers Buffett her best friend and plays bridge with him weekly, resigned in October 2015, with the seeming subtext being their discomfort with the Valeant position. This is illustrative of the general struggle to push back against aggressive behavior of control fraud due to the ephemeral appearance of excellent financial results. The WSJ reported on Ruane Cunniff’s extensive research not just into Valeant, but specifically into Philidor and their practices, which was not enough for them to change their mind.

Ruane, Cunniff & Goldfarb Inc., manager of Sequoia Fund Inc., said it reached out to former employees of the Philidor Rx Services LLC mail-order pharmacy that almost exclusively dispensed Valeant drugs and sought to speak with them about the pharmacy’s work.

Staff from Ruane Cunniff paid ex-employees and pledged to keep names of those they spoke to confidential, said David Poppe, the firm’s president. He said the firm paid $1,000 to talk with one former employee for two hours and discussed giving that ex-employee several thousand dollars if the person would keep Ruane Cunniff exclusively apprised “about what was happening at Philidor,” though the firm eventually decided against entering into any further arrangement.

“We went into our own due diligence phase, and we reached out to a number of people. Some of them wanted to be paid for their time, and we did pay them for their time,” Mr. Poppe said. He said Ruane Cunniff told every person it spoke with that it “did not want them to violate any nondisclosure agreements they had signed with Philidor.”

…

Sequoia has “always had a history of buying and selling based on its own research, not on what is popular or unpopular,” said Sequoia board Chairman Roger Lowenstein.

On Oct. 28, Ruane Cunniff sent a letter to its shareholders defending Valeant and its relationship with Philidor. The letter said “there is no legal reason Valeant can’t advise, control or own Philidor.”

Ruane Cunniff said in the letter that “we work hard to understand Valeant and its business model.”

“In our view, Valeant is an aggressively managed business that may push boundaries, but operates within the law,” the letter said.

The above article is after many facts were public about improprieties, which included Valeant employees using aliases when conducting Philidor business. The lengths gone to hide the nature of the practices should be a strong enough indication that the consequence of the actions being discovered were known to Valeant to be very negative for the business. RCG’s acceptance of the actions show the extent to which temporary profits can cloud the judgement of people who are well positioned to identify that unsustainable practices are behind the business activity.

SPACs

All the key ingredients for control fraud were actively amplified in the 2021 SPAC boom in a way that shows the market’s sentience to actively offering the control fraud cocktail deceptively packaged as a great investment opportunity. This is arguably the most comparable set of circumstances to the S&L control fraud. It happened in a wave with common behaviors and patterns that enriched certain parties without attendant business success. It also incorporates the more nuanced practices of Carvana or Valeant that show the adaptive nature of control fraud. Rather than focus on any one SPAC in particular, the focus will be on the ways the SPAC structure offers the opportunity to implement and amplify all the key ingredients of control fraud without having to engage in any activity at all.

Ease of Control

SPAC sponsors immediately gained control simply by raising money. A SPAC is explicitly formed to pursue a deal. Sponsors get promoter shares upon the completion of a deal, so they stand to make money simply by closing a deal. While there is a voting process to approve a deal that the sponsor finds, the general euphoria in the market for SPACs at the time made it highly unlikely that any deal would be rejected.

The initial equity funders of a SPAC received warrants alongside the purchased shares. The warrants would appreciate in value if the shares rose, while the shares retained the right to get their money back if the deal didn’t generate the expected enthusiasm. In theory, an initial backer could get all of their money back by exercising the redemption feature on the common shares (e.g. voting against the deal), but still obtain upside from the warrant appreciating.

Warrants are highly leveraged to the share price, which could be expected to skyrocket upon announcing a deal during a euphoric market episode. The warrants explicitly harkens back to the behavior of Michael Milken in the 1980s. He was a facilitator to S&L control fraud as one of the main capital markets access points for Charles Keating’s Lincoln Savings. Milken would raise debt through Drexel for a company the condition of warrants being issued alongside the debt, except Milken would keep the warrants for himself while the junk debt ended up on the balance sheets of companies like Lincoln. It is not surprising that Milken’s family office identified the opportunity in providing initial funding for SPACS and getting founder warrants in the process.

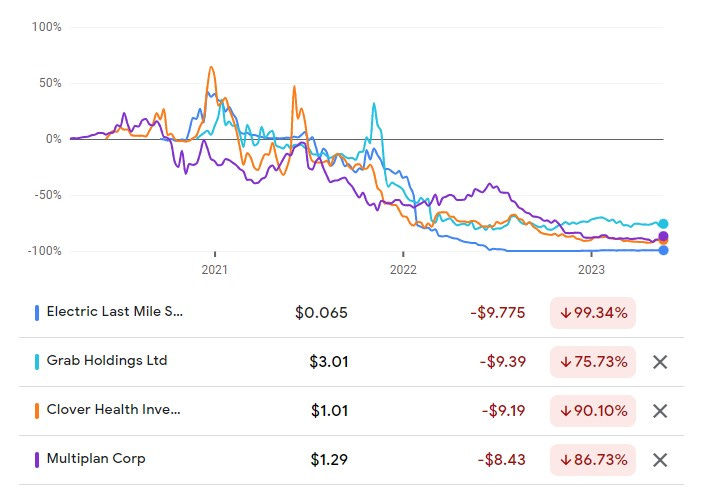

Milken was not alone in being enticed by these warrants. Altimeter, a venture capital firm, raised a SPAC that did a transaction with Grab, a Southeast Asian delivery app. The WSJ reported that the promoter warrants were given directly Altimeter partners and SPAC directors in connection with the deal. Grab continues to lose a lot of money and the shares are down 70%, an indication and some confirmation that this transaction occurred largely for the benefit of the SPAC promoters.

“Veteran dealmaker Michael Klein and his team were awarded $275 million worth of stock last month for merging their SPAC Churchill III with healthcare services firm MultiPlan Corporation in an $11-billion deal by only investing $25,000, according to SPAC Analytics. Klein’s team separately invested $23 million to receive warrants, or options to purchase shares at a certain price, in the company.

The combined company’s shares are now trading at 25% less than when the deal closed amid concerns over growth prospects. Yet Klein and his team are still in the black by more than $200 million, because the shares cost him only a tiny fraction of what investors paid.

A spokesman for Klein declined to comment.

Another prolific SPAC sponsor, Chamath Palihapitiya, is in line for a stock payout that on paper will be worth $207 million after investing $25,000 of his own money in a $3.7 billion merger with U.S. insurance startup Clover Health. He also invested $16.4 million to receive warrants in the combined company.”

Both Multiplan and Clover are down 90% from their SPAC conversions. The windfalls of the sponsors can be substantial even if the company winds up with credible short seller scrutiny, as Multiplan and Clover have.

These twins forces – sponsors who could quickly make a lot of nearly free money upon the approval of a deal and initial backers who were presented with a close to risk free proposition – creates an adverse selection machine, much in the way that the ADC loans at control fraud S&L’s were structurally low quality.

Rapid Growth & Aggressive Accounting

It is impossible to separate rapid growth from abusive accounting with SPACS. The presentation of rapid growth stems from aggressive accounting in the form of completely made up forward projections. A key feature of the SPAC mania is that promoters merely had to allude to a magnificent future rather than going through the lengths of giving some substance to the operations like Carvana or Valeant had to in order to attract interest. SPACs combine the fabrication of growth like S&L’s engaged in ADC lending with the very permissive attitude towards statements made in presentations that Valeant and Carvana demonstrated.

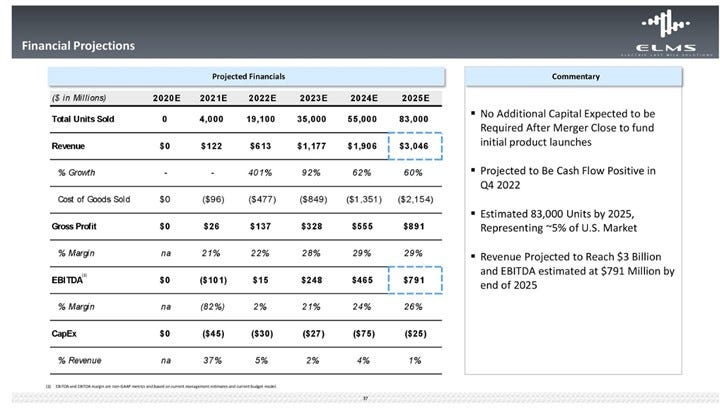

There has been research that SPACs providing overly ambitious revenue guidance occurs at a systematic level, but looking through nearly any SPAC presentation shows varying degrees of absurdity in presenting fast growing and highly profitable companies several years out. Electric Last Mile Solutions, whose financial projections are below, is one of 7 SPACs that went bankrupt within a year of completing a transaction. It should be noted that ELMS declared Chapter 7 bankruptcy. It was liquidated rather than reorganized, as one might expect if there was any value in continuing to fund the business plan.

Lax Regulation

Similar to Valeant’s presentations, numbers in SPAC presentations are unaudited and often conveyed fantasy. Part of the basis for this is that SPACs are explicitly designed to circumvent the IPO process, which has much more rigorous disclosure requirements and regulatory oversight in general. The biggest regulatory oversight was with the most abusive situations – where the SPAC was taking over an essentially nonexistent business with limited operational history, such as ELMS. This attracts science project companies that likely couldn’t pass through the IPO process successfully. For all intents, companies like ELMS never possessed credible substance.

The specific loophole available to SPACs and already public companies but not IPOs is the PSLRA (source):

There is a widely held understanding that the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act’s (PSLRA) safe harbor applies to SPACs whereas it does not apply to IPOs.110 The safe harbor provides that, when accompanied by appropriate cautionary language, a company making a forward-looking statement without actual knowledge of its falsity will not be held liable in a private action brought under the securities laws. Projections are commonly included in SPACs’ investor presentations and proxy statements, and are essentially never included in IPO prospectuses. This difference in treatment is not the result of a deliberate policy decision by Congress or the SEC. The PSLRA’s safe harbor excludes “blank check companies” from its coverage. But a few years earlier, the SEC had defined “blank check companies” very narrowly to target penny stock fraud, and SPACs were designed to fall outside that definition.

There has been little in the way of pushback from the SEC on any specific SPAC for its actions because it doesn’t seem like any laws were broken. The SEC has initiated a lawsuit over disclosure around conflicts with one specific SPAC promoter. The SEC proposed changes in March 2022, including ones to how financial projections are disclosed, which is an admission that the regulations were too weak. While the PSLRA safe harbor exists for Carvana and Valeant, it is more distinct as lax regulation with SPACs because there is no alternative in the form of SEC filings to contradict the presentations.

Conclusion

The combination of four relatively simple ingredients can create a complex adaptive system that is an effective vehicle for extracting money from the securities market. This occurs at individual companies or in waves, which shows the phenomenon is scale invariant, further bolstering the case that this formula reflects an enduring dynamic in the rhythms of financial markets. Control fraud is a very plausible explanation to a lot of behavior in public markets that otherwise gets dismissed as one off episodes with no applicable lessons.

Any individual component of a business model can be amplified by other components to facilitate a flattering appearance – the way lax regulation may temporarily spur rapid growth, or how ease of control increases the use abusive accounting. Attention is often solely focused on positive flywheels. The inverse of characteristics that amplify negative outcomes is equally valuable to study. No company will ever highlight a destructive flywheel. The reality of negative flywheel can be distorted to convey the fantasy of a positive flywheel as seen with Carvana and Valeant.

The reciprocal mechanism of simultaneously concealing and amplifying risk is a dangerous feedback mechanism to encounter with naivety. The ripest ecologies for control fraud possess a dependence on it not being brought to attention, particularly if the extraction mechanism is selling shares or cashing in on options packages. If uneconomic undertakings generate an ephemeral increase in the share price, then management’s commitment to it is likely to increase.

It is not difficult to identify a control fraud dynamic at work if you are aware of the concept. The likelihood that benign explanations are correct is very low when all four ingredients are identifiable. The negative implication of each ingredient is individually debatable and open to interpretation, but the benefit of the doubt shrinks as more of the ingredients appear and should probably disappear when all four are identified.

Nearly every piece of evidence in the above examples was contemporaneously available. Much of it was prominently featured in newspapers and major periodicals prior to significant drops in share prices. Prominent investors with a variety of investment approaches have nevertheless been deceived by control frauds. This is just a bemused observation.

Similar to a magic trick, it’s still very valuable to identify if one is being performed without identifying the precise mechanisms at play. Control fraud is likely to prove an enduring phenomenon as long as humans have emotions. A useful antidote to FOMO is increasing your ability to identify how certain mechanisms increases the likelihood control fraud, which is why I have belabored some of the details in the case studies. It is arguably harder to be deceived when focusing on specific mechanisms rather than seeking a broader inoculation against alluring narratives or charismatic leadership. Increasing familiarity with this concept should better equip anyone to respond to the changes in the forms control fraud takes.

Fantastic work! The idea of "ecological conditions" is a useful lens through which to view any aberrational price movements. Market structure have changed dramatically, and shareholder constituencies are more important than ever. Companies can use the high-growth vernacular that appeals to Cathie Wood, or the FCF-compounder language that attracts certain investors. Sometimes, the positioning of an equity in the market, gives management broader discretion and less oversight by shareholders provided they maintain that positioning (a high-growth disruptor, "Outsiders"). AI is creating a new ecological condition; companies can position themselves as AI-beneficiaries in a multitude of ways. Shareholders in turn, can graft their own optimism about the future on that general narrative even though it currently lacks specific or tangible business outcomes.