Valuable lessons in how markets work can be found in their breaking points. The Hunt family’s attempt to corner the silver market is a worthwhile episode to examine. Beyond Greed provides a solid base to understand the period beyond, “the Hunts bought a lot of silver.” The behavior of all actors in markets – individual investors, brokers, exchanges, regulators, the Fed, and banks – can be observed in a way that gives a deeper appreciation for the mechanisms that can drive price movements.

Thesis

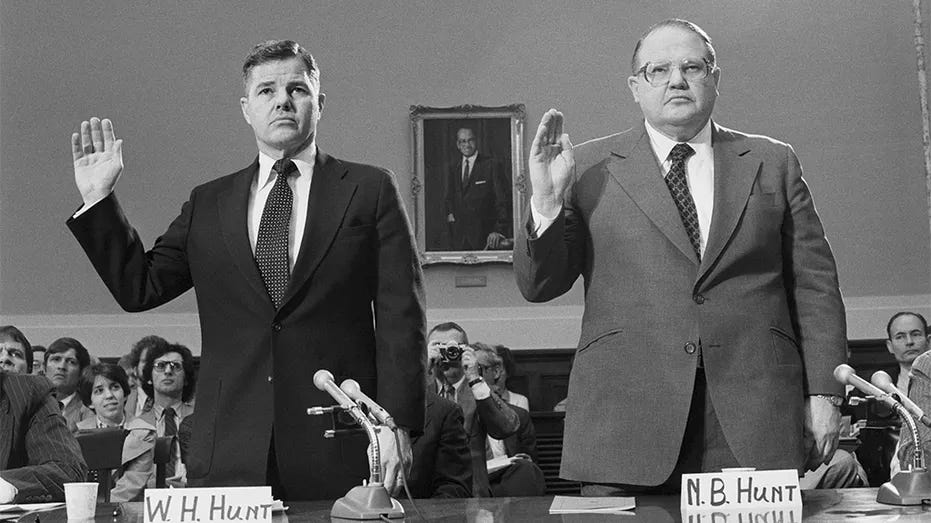

The Hunt brothers, Herbert and Bunker, had a solid thesis for investing in silver. Broad trends unfolding over 1960s and 1970s pointed to a high probability of an extreme supply and demand imbalance in silver, which would result in higher prices.

Most of the world’s silver is not produced at dedicated silver mines but as a byproduct of mining copper, lead, or zinc mining. Lower cost surface mines were depleted and had to be replaced with underground deposits that were more expensive to mine. The sale of US government silver holdings that had been accumulated since 1934 was a temporary source of supply that would eventually be exhausted. Silver supply could theoretically come from reclamation – melting down coins, silverware, or jewelry – but this would require a high enough price to garner attention of the numerous and disparate holders (one source of illegible silver supply was distributed across India and had to be smuggled out of the country to Dubai before it could enter global markets).

Silver demand had been steadily increasing in the preceding years and showed no signs of abating. It was finding applications in photography, electronics, medicine, and aviation. Silver was critical to the products in these markets but a small portion of their costs, which supported the belief that a huge increase in prices would not affect demand. Another source of “demand” was generated by the Bretton Woods monetary system collapsing and attempts to identify assets that could protect against inflation.

Execution

The Hunts started buying silver bullion and futures in 1972 and were enthusiastic promoters of the idea to other people. By December 1973, they had contracts for 35 million ounces of silver, about 10% of silver supply. From December 1973 to February 1974, a brief squeeze sent silver from $3 to $7, which seemed to serve as a brief introduction to the Hunts of what could potentially be done.

The Hunts spent several years courting followers, especially in the Middle East, while also steadily increasing their holdings in silver. The Hunts bought control of Greater Western United, a beet sugar refiner, in 1975. They directed the trading subsidiary to start trading in silver, with the company taking delivery of 21 million ounces of silver in June 1976, about 5% of annual silver consumption at the time. As insight into their temperament and methods, the Hunts had accumulated 8x as many soybean contracts as position limits allowed by spreading the holdings across family members’ accounts in 1976. This specific episode is better covered in Merchants of Grain.

The Hunts bought 21 million bushels of soybeans compared to a position limit of 3 million. Cook Industries, a commodity broker, was short soybeans while the Hunts were buying. The Brazilian government, major exporters, put a tax on soybean exports to keep global prices high at the same time too. The Hunts knew that Cook was short soybeans because a distant cousin, J. Stuart Hunt, sat on the board of Cook. Cook called the CFTC, which had only been formed in 1974, to complain, but the commissioner there had just come from working at Cook. The CFTC filed a lawsuit against the Hunts, where the judge agreed they violated position limits but did not engage in manipulation.

In the middle of 1979, they convinced Saudi investors to contribute to a Hunt managed JV called International Metals Investment Company (IMIC) to purchase silver. IMIC’s purchases of silver showed up on Commodities and Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) reports starting in August, with silver having gone from $6 to $9 per ounce in the first half of the year. IMIC was not the sole entity trading at the Hunts’ behest or that of their associates – the Saudis bought through numerous Arab front men and the Hunts bought through accounts opened in the names of various family members.

Silver prices were already up 65% from the start of the year by the time IMIC started buying, but prices continued to increase in September, going from $10 to $18 an ounce. The New York based commodity exchange, Comex, saw contracts settled for physical silver that was taken out of its warehouse and flown to Switzerland. This was seen as particularly odd, because the frictional costs would have been much lower to exchange the contracts for ones on the London Metal Exchange (LME) and then moved to Switzerland.

Moving physical silver around isn’t outright manipulative, but it sets up the settlement of futures contracts in coming months to confront a supply deficit if the holder opts for physical settlement. This was the case with a large number of December contracts relative to the inventory in the Comex warehouse. The Hunts’ futures contracts were concentrated around December 1979, January 1980, and February 1980. These would mature into a localized shortage of physical silver in the warehouses that was mostly the making of the Hunts.

Another recurring observation in the silver market was a large volume of orders being placed in London. London is relatively less liquid than the Comex or Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT), but due to time differences it sets the tone for trading later in the day (like modern day overnight trading). The LME had less government regulatory oversight and greater privacy protections compared to the US, which also cast some broader uncertainty on silver markets because the intention of the large purchases was harder to discern.

Comex kept raising margin requirements throughout September. One contract represents 5,000 ounces of silver, so at $10 per ounce, a contract would be worth $50,000. On September 18, Comex raised the margin requirement to $20,000 with silver at $18.30 and a single contract worth $91,500. The price increase of silver fully compensated for the higher margin requirements on the long side, but not for the shorts.

The opposite side of market ended up exerting upwards pressure on the market as well. Metal brokers who owned physical silver used futures markets to hedge and were increasing their short positions in the market. This meant that players with short positions on the market and long positions off it had to post increasing capital in order to maintain their positions. The limited size of their balance sheets pushed them to close out their short contracts by exchanging physical silver holdings for them. The Hunts were often on the other side of these transactions, which meant shorts exited the market and the supply controlled by the Hunts increased further.

Intervention?

The CFTC had the information in October showing that large silver positions could be traced to various brokers representing the Hunts – in reality the brothers Bunker and Herbert were behind all the activity, but accounts were being opened in the name of a constellation of family members as well. The CFTC was in the middle of a lawsuit against the Hunts for exceeding position limits in soybean futures in 1976 as well, so they had some understanding of the type of people involved. The CFTC was not fast to make decisions and the preference was to remain uninvolved in the market.

The CFTC’s bureaucratic passivity was matched by the financially incentivized kind from Comex. Comex had the highest exposure to silver trading of all the commodity exchanges. Since it was owned by its members, that meant the organization’s underlying priority was to maintain trading volumes, which supported the income of members. While Comex kept increasing margin requirements the only part of the market forced to actively respond to this were the shorts.

Silver prices were flat for most of October, but then broader events impacted the silver market. The American Embassy in Iran was stormed in early November, which impacted oil prices and the prospects of inflation. In early December, media reports came out about how the Hunts and the Saudi Royal family were going to accumulate silver and refuse to sell it until it reached $25. Then a rogue trader for the Peruvian mining export department was caught in a large speculative short position, which was liquidated at $25.50 an ounce. The USSR invaded Afghanistan in late December 1979. Silver ended 1979 at $29.30.

Silver prices increased to $37 on Jan 4, 1980. Comex became concerned about having enough silver inventory to settle monthly contracts, largely due to the Hunts having taken physical delivery of silver and owning a lot of contracts that settled in January and February. The Hunts had assured the CFTC commissioners that they didn’t intend to take physical delivery during discussions in the preceding months, but this was no longer credible. At this point the Hunts and “foreign investors” had 50% of Comex’s silver inventory and 70% of CBOT’s. The CFTC estimated that the Hunts and associates owned 77% of the world’s estimated privately held silver on January 8.

Comex announced a position limit of 500 contracts for any given month, which would start in February. The limit represented 2,500,000 ounces of silver, which would be worth ~$90m at prevailing prices. The Hunts and associates controlled about 18,000 contracts worth ~$3.3bn. Shortly after the position limit announcement, Comex capped new speculator positions at 50 for the spot month and 251 for longer dated contracts. A flurry of new accounts opened to circumvent the intent.

Silver went to $42.50 on January 14. The market was aware that yet another metals broker, Engelhard, was facing massive margins calls. Engelhard also owned a silver refinery that was bringing scrap silver to the market. Engelhard would lock in a refining margin by shorting contracts, but this meant they would have to post margin. Engelhard reached an agreement with the Hunts to sell them silver at $35 an ounce in late March and late July 1980, which solved their margin crunch, but increased the portion of supply held by the Hunts.

Silver went above $50 on January 18. Since the position limits proved ineffective, Comex announced that trading was now for liquidation only. This took speculative players out of the market completely. The price fell to $44 on January 21 and then $34 on January 22. The next several weeks saw a lot of volatility with prices bouncing between $30 and $40 an ounce.

De-Bache-le

On March 14, 1980, the Fed announced a special credit restraint program where banks were “asked” to stop financing speculative holdings of precious metals. For context, gold had gone from $200 per ounce at the start of 1979 to a peak of $850 in early 1980, a 325% gain compared to silver’s 700% gain over the same time period. By the middle of March, silver was trading for $23. The prime rate went to 20% at the same time, which increased the cost of financing the remaining silver as margin loans were typically floating rate. In contrast to the previous months, the threat of inflation was receding, the ease of financing speculative positions was reversing, and the cost of financing existing positions was increasing. This was a sharp and sudden reversal in many of the factors driving up silver.

In aggregate the Hunts had borrowed close to $1.3bn to finance 70m ounces of silver (~$18/oz of debt). One of the key financing partners for the Hunts was Bache, a brokerage house. While the Hunts borrowed from several banks, Bache in particular had many reasons to be generous with the Hunts. The Belzbergs were buying shares of Bache in early 1979 and were considered hostile to management. From October 1979-March 1980, the Hunts bought up 6.5% of the Bache and were friendly to management.

Bache returned the favor with favorable margin terms for the Hunt silver purchases. Bache had also hired the Hunts’ key broker from another firm that wasn’t as accommodating to the Hunts. At Bache, the broker was guaranteed 50% of the revenue from the Hunt relationship. This broker had previously helped the Hunts with the soybean contracts in 1976 that violated position limits.

As late March arrived, the Hunts were supposed to start paying for silver deliveries from Engelhard. The Hunts also received a margin call from Bache that they could not meet. Silver was trading for $21 per ounce on March 25. Bache started to sell the Hunts’ collateral, which drove down the price of silver to $11 on March 27. The only collateral Bache didn’t sell was the Hunts’ shares in Bache. Engelhard wanted to be paid as well and the Hunts tried to barter with oil concessions.

Since various banks were now exposed to losses from financing silver trading through lending to Bache and directly to the Hunts, Volcker became more directly involved. A tense weekend was spent hashing out a deal between the Hunts, Engelhard, all the banks financing the Hunts, Volcker, and the Treasury Secretary. By 5am on Monday, March 31, Engelhard accepted a 20% in a North Sea oil concession owned by the Hunts.

The Hunts now owned about $1.3bn worth of silver and had debt of $1.1bn tied to the position. The Fed had the banks agree to lend money to Placid Oil, a Hunt controlled oil company, that would then lend the money to the Hunts to repay the banks. Placid pledged oil properties worth $3bn to the banks, which removed any loan to value concerns for the banks. The combination of stopping any speculative buying, forced speculator sell downs through financing terms changing cascading into margin calls, and the Hunts running out of money put an end to the silver corner. The Hunts then spent several years in litigation and bankruptcy sorting out their liabilities. The Saudis and various connected parties were rumored to have an average cost of $25 per ounce and suffered large losses that various European banks ended up partially swallowing.

Reflections

This episode started off with a very good investment thesis. There were unique quirks to silver that made it very resistant to a rapid supply response. It was a small but critical portion of the bill of materials that meant the price could be increased dramatically for a sustained period of time before incremental supply brought prices back into a calm equilibrium. The US was selling down silver stocks over a multiyear period, a finite supply that would distort prices downwards in the medium term. Inflation had increased the nominal cost of new mines, which provided another boost to the price needed to exceed the cost of marginal supply. A steady increase in demand meant higher prices were a matter of time. Even without getting into monetary theory, there was a strong fundamental case in support of much higher prices. This should all stand on its own merit, but if you want an appeal to authority, note that Buffett clearly kept these dynamics in mind for close to 20 years and acted on it when the time was right.

Silver returned to mid-single digits per ounce by the mid-1980s. The price of silver stayed around that level until 2004. Even ignoring the obvious lesson of not overstaying a squeeze in the short term, the seemingly solid case for much higher prices did not cause a step change over the long term. This reinforces the peril of ignoring the price paid when investing on the basis of broad multiyear theses. The thesis was identical in 1973, 1976, and 1979, but the profitability of acting on it was very dependent on the price paid.

The September 1979-January 1980 period is worth reflecting on as if a contemporary market observer. Silver went from $6 to $10 in the first half of the year, already a sizable move. By the start of October it was close to $18. A 300% rise would have been a really enticing entry point for a short seller, but the price still went to $29 by year and then all the way to $50 in January. There were as many “obvious” entry points to short silver as there were times you would likely capitulate. Knowing the squeeze was on, or more broadly any type of manipulation, isn’t really insightful. The only opening for an outsider to “safely” short silver was once Comex and the Fed completely stopped speculative buying. The exchanges and regulators were incredibly reluctant to act and only did so with things very close to the precipice of disaster.

An investor is better off avoiding political timing in the same way they are with market timing. The Hunts weren’t wrong to view their experience buying up soybean contracts as tacit permission for aggressive behavior in futures markets. This same pattern repeated itself with Bill Hwang in Archegos. While in a twist of fate Hwang’s hedge fund took a massive hit shorting Volkswagen into its squeeze, he eventually shut it down due to being investigated for insider trading from 2010-12. He faced no serious penalties. He may have judged that further aggressive behavior didn’t face serious regulatory risk, such avoiding disclosure requirements by obscuring holdings through the use of lightly regulated swaps. In the case of Archegos, its undoing was Viacom bringing more supply of shares to the market and undoing the squeeze that had been occurring in its stock.

Playing the Money Game in a Squeeze

One of the individuals who profited from shorting the squeeze was Armand Hammer of Occidental Petroleum. He owned a stake in a high cost silver miner acquired in 1976. He received a study on the mine in November 1979, which could start production in early 1980 with a cost of $9 per ounce. Owning a mine meant Hammer could participate in the commodity exchanges as a hedging participant, which is an advantage given the lower margin requirements than speculators. This reduced Hammer’s risk of a disastrous margin call outright, but more importantly owning a mine also meant he knew what his cost to deliver physical product to satisfy any contracts would be. He started shorting silver on January 8, 1980. One lesson in this is to reemphasize the dynamic impact of financing structure, as the corner itself failed on weak financing and shorting it successfully was best done from a position of uniquely low cost financing. Another lesson is it helps to be lucky with timing. The metagame here is also reminiscent of Beal Bank or Buffett’s Japanese trading house investment.

An outsider without a proprietary advantage still retains a very powerful ability in markets by doing nothing. To channel Sklansky and The Theory of Poker, “In all poker games it is far better to be last to act, primarily because it is generally easier to decide what to do after you have seen what your opponents have done.” In the case of the silver squeeze, this does not simply mean the Hunts or the metal brokers, but also the CFTC, the exchanges, the banks, and the Fed. Even when these players weren’t playing a visible role in the silver market, that was still an active choice that had an impact. An outsider will never be in the position of acting last in a squeeze with the exception of having perfect timing. An individual not sitting down at this table has no influence on the market, but it also removes the market from having an influence on the individual. Even if you could financially and psychologically handle extreme volatility for a period of time, you still would be at a big disadvantage by not being able to determine the timing of all the players acting.

There is a similarity and an important difference in the silver squeeze and oil going negative during Covid. The logic of both price movements operated on physical factors reflecting mechanical aspects of markets rather than any financial formula or broader economic concept. While uncommon, it isn’t appropriate to view these episodes as illogical or even as a market failure. Oil wells couldn’t be shut down fast enough to compensate for the sudden drop in demand. Oil had to physically go somewhere to the point where sellers paid buyers. This is the inverse of the silver squeeze, where a major driver was the lack of physical supply to fulfill all the contracts maturing in a given month.

What the silver squeeze lacked that the oil setup didn’t was the one factor investment decision that arises from a forced seller. While there was a proprietary physical angle with access to storage, outsiders could have purchased out of the money short term puts if they quickly recognized oil could go negative. This is a far more pleasant position to be in than shorting a squeeze – i.e. taking the other side of a forced buyer or “buying force” – because there is no margin requirement and forced sellers will have a finite amount of selling to do. While not a viable strategy to continuously pursue, an assortment of panic playbooks that appreciate the dynamics of forced selling can be useful in generating idiosyncratic profits, such as buying busted mergers where arb funds try to exit all at once or looking at preferred equities that suspend dividends. The reason to think in such broad terms is that future opportunities of this nature will always have different surface level circumstances rather than conform to anything contemplated in a textbook. The shift in spinoffs from typically unlocking value in a subsidiary that may see an initial sell off in the shares to ways to rid a parent company of various liabilities that come to light several years after the spin is a good reason to think in terms of forced sellers rather than a particular financial structure.

Conclusion

Following the unfolding of the 1979-80 silver squeeze offers more lessons than a summary of them. Similar to the Taiwan Bubble or control fraud, the market mechanics are worth examining because they are typically present in varying combinations of the same ingredients in other extreme market periods. You can better comprehend the dynamics at play in the 2022 nickel squeeze, the 2021 Archegos squeeze, the recurring GameStop squeezes, or nearly any squeeze when using the broad blueprint provided by studying the Hunt Silver squeeze. Rather than offer a money-making playbook for participating in squeezes, these are often very good ways to substantiate the choice to remain on the sidelines when they unfold in the future.